- Home

- Patti Smith

Devotion_Why I Write Page 2

Devotion_Why I Write Read online

Page 2

The following morning before rejoining Alain and Aurélien at the train station, I take a last walk, discovering a sequestered park presided over by an imposing statue of Neptune. I climb uneven stone steps up a slope that opens onto what appears to be a botanical garden, with a number of squat palms, and a variety of trees. As I wander about, an unexpected though familiar giddiness overcomes me, an intensification of the abstract, a refracting of the mental air.

The sky a pale green, the atmosphere releases a relentless flow of images. I take refuge on a bench protected by shadows. Slowing my breath, I unearth my pen and notebook from my sack, and begin scribbling, somewhat involuntarily.

A white dragonfly plucked from a music box. A Fabergé egg encasing a miniature guillotine. A pair of skates twisting in space. I write of trees, a repetition of figure-eights, the magnetic pull of love. Not certain of how much time has passed, I cease writing, rush past the curving back of Neptune, down the stone steps, hurrying to the nearby train station. Alain regards me quizzically. Aurélien asks me whether I took any photographs. Only one, I say, a picture of a word.

On the train I continue to write feverishly, as though resuscitated from a sea of memory. Alain glances from his book and looks out the window. Time contracts. We are suddenly approaching Paris. Aurélien is sleeping. It occurs to me that the young look beautiful as they sleep and the old, such as myself, look dead.

3

A particular joy of good weather, an amiable lightness I easily succumb to. I go into the Saint-Germain church where boys are singing. Communion perhaps. There is a solemn delight in the air and I feel a familiar desire to receive the body of Christ but do not join them. Instead I light a candle for my loved ones and the parents who lost children at Bataclan. The candles flicker before Saint Anthony holding a babe, both covered with decades of delicate graffiti that make them seem alive, animated by the inscribed pleas of the living.

I take a last walk up the Rue de Seine, or is it down? I don’t know, I just walk. There is the odd familiarity that keeps tugging at me. A long-ago sense of things. Yes. I have been on this same path with my sister. I stop and look at the narrow lane of Rue Visconti. I had so thrilled at my first sight of it that I ran the length and jumped in the air. My sister took a picture and in it I see myself, forever frozen in air full of joy. It seems a small miracle to reconnect with all that adrenaline, all that will.

VOLTAIRE. SQUARE HONORÉ-CHAMPION

At the top of Square Honoré-Champion, another flash of recognition. Toward the back of a rather pedestrian garden I recognize a statue of Voltaire, the first thing I photographed in Paris. Amazingly the little garden remains as pristine and uninteresting as it was half a century ago, but Voltaire, much changed, seems to be laughing at me. The details of his once benevolent face, worn away by time, appear darkly comic, macabre, as slowly decomposing he stoically presides over his unchanging domain.

I remember seeing Voltaire’s cap in a glass case in a museum somewhere. A very humble flesh-colored lace cap. I harbored an intense desire for it, a strange fascination that lingered coupled with a superstitious notion that the wearer might access the residue of Voltaire’s dreams. All in French of course, all of his period, and at that moment it occurred to me that dreamers through time dreamed of those in their own epoch. The ancient Greeks dreamed of their gods. Emily Brontë of the moors. And Christ? Perhaps he did not dream, yet knew all there was to dream, every combination, until the end of time.

My duties to Gallimard accomplished, I board the Eurostar to London. On the train I rewrite some of the passages of the story I had begun in the quiet park in Sète and continued on the racing train to Paris. Initially I wondered what prompted me to write such an obscure, unhappy tale. I did not wish to dissect with a surgeon pen, but as I reread I was struck by how many passing reflections and occurrences had inspired or permeated it. Even the most insignificant reference I saw clearly as if highlighted. For instance, a perfect plate of fried eggs was echoed in a round pond. I had drawn certain aspects of Simone’s countenance for Eugenia, my young heroine: her intellectual flexibility, strange gait, and innocent arrogance. Yet other aspects I reversed. Simone shuddered at the touch of another, while Eugenia blatantly craved it.

At St. Pancras International I took yet another train to Ashford, the last length of my journey, to find Simone Weil’s grave. We passed row houses, a lifeless landscape. I noticed the date on my ticket was June 15, the birthday of my late brother Todd. His only child a daughter called Simone. I immediately brightened. Only good could happen today.

Arriving, I found a coffee stand, then looked for a taxi. The sky was deepening and there was a strong chill in the air. I removed my camera and watch cap from my suitcase. The taxi ride took about fifteen minutes and I was dropped off in front of the entrance of the Bybrook Cemetery. I half expected there would be a little stone carriage house or someone distributing maps, but there was no one. Only a groundskeeper cutting weeds in a veil of light but steady rain.

The cemetery was more sprawling than I anticipated and I had no idea where Simone might be. I walked up and down paths, somewhat daunted. The light was low. Only noon, yet more like sundown. I took a few photographs. An embedded cross. An ivy-encrusted tomb. Nearly an hour passed. It continued to rain. A part of me was succumbing to the notion that it was an impossible task when I suddenly remembered she was buried in the Catholic sector. I found an area with many likenesses of Mary and crosses everywhere, but no trace of Simone. I searched an area dense with statues. The sky grew darker. I sat on a bench somewhat demoralized. Would Simone approve of this pilgrimage? I thought not. But I had lavender from Sète in an old handkerchief to leave her, small bits of France, and recalling her love of her homeland, her longing to return, I pressed on.

I looked up at the menacing clouds.

I entreated my brother.

—Todd, can you help me? I’m alone on your birthday and searching for someone named Simone.

I felt his hand guiding me. On my right was a wooded area and I felt compelled to walk toward it. Suddenly I stopped. I could smell the earth. There were larks and sparrows, a small shaft of light that appeared, then disappeared. I turned my head with no exalted pause and found her, in all her modest grace. I opened the bellows of my camera, adjusted my lens and took a few pictures. As I knelt to place the small bundle beneath her name, words formed, tumbling like a nursery song. I felt helplessly at peace. The rain dissipated. My shoes were muddied. There was an absence of light, but not of love.

4

Fate has a hand but is not the hand. I was looking for something and found something else, the trailer of a film. Moved by a sonorous though alien voice, words poured. I went on a journey lured by a jukebox of lights conjuring a symphony of reference points. I threaded a world that was not even my own, wandering the abstract streets of Patrick Modiano. I read a book, introduced to the mystic activism of Simone Weil. I watched a figure skater, wholly beguiled.

I began to write the piece entitled Devotion on the train from Paris to Sète. Initially I thought to compose a heightened discourse between disparate voices—a sophisticated, rational man and a precocious, intuitive young girl. I was interested to see where they would lead each other, forming an alliance in a realm of opulence and obscurity. I had also kept a loosely formed travel diary: bits of poems, notes, and observations for no particular reason save to write. Looking back on these fragments, I am struck with the thought that if Devotion was a crime, I had inadvertently produced evidence, annotating as I went along.

Most often the alchemy that produces a poem or a work of fiction is hidden within the work itself, if not embedded in the coiling ridges of the mind. But in this case I could track a plethora of enticements, a forest of firs, Simone Weil’s haircut, white bootlaces, a pouch of screws, Camus’s existential gun.

I can examine how, but not why, I wrote what I did, or why I had so perversely deviated from my original path. Can one, tracking and successfully collaring a c

riminal, truly comprehend the criminal mind? Can we truly separate the how and the why? A few moments of self-interrogation forced me to acknowledge the strange remorse I felt following the writing of it. I wondered, since I had birthed my characters, if I was mourning them. I also considered whether it was a quality of age, for when young I wrote with reckless abandon on any subject without a shred of moral concern. I let Devotion stand as written. You wrote it, I told myself, you can’t wash your hands of it like Pilate. I reasoned these concerns philosophical, or even psychological. Perhaps Devotion is merely itself, unfettered by worldview. Or perhaps a metaphor drawn from the untraceable air. That is my final conclusion, one that is absolutely meaningless.

Back in New York City, I found it difficult to chemically re-adjust. More than that, I suffered bouts of nostalgia, a yearning to be where I had been. Having morning coffee at Café de Flore, afternoons in the Gallimard garden, bursts of productivity on a moving train. I was on Paris time, dropping off to sleep in the late afternoon, waking suddenly in the long, still night. On one such night I watched The Secret Garden. A crippled boy made to walk again through the fervent will of a lively young girl. There was a time when I imagined I would write such stories. Like Sara Crewe or The Little Lame Prince. Orphaned children negotiating a darkness eclipsed in brightness. Not the type of story I found myself writing breathlessly on a Paris train without remorse.

Silence. Passing cars. The rumble of the subway. Birds calling for dawn. I want to go home, I whimpered. But I already was.

BYBROOK CEMETERY, ASHFORD, KENT

Ashford

Deep in the earth your little bones

your little hands your little feet

in restless repose unfastening loops

calling for bread and potato soup

a shock of light struck the valve

milk of the lamb poured from the side

and a terrible mist rose underfoot

you were all snow white

and I the seventh dwarf

prepared to serve you

there were wafers enough

for every living thing

who offered his tongue

there were no more cries

there was no fasting heart

Only the relics of consumption

wrapped in the silk of existence

Devotion

1

He first noticed her on the street. She was small with porcelain skin and thick dark hair with severely cut fringe. Her cloak seemed thin for winter and the hem of her uniform uneven. As she brushed past he felt the sting of intellect. A petite Simone Weil, he remembered thinking.

He saw her again a few days later, heading away from the other students, rushing to make their class. He stopped and turned, speculating on what drove her in the opposite direction. Perhaps she felt ill and broke form to return home, but her determined air suggested otherwise. Most likely a forbidden rendezvous, an eager young man. She boarded a trolley. He didn’t know why he followed her.

Absorbed in her own trajectory, she failed to notice him when she reached her destination. He stayed several paces behind as she approached the bordering forest. Unwittingly she led him down a stony path to a thick grove obscuring a large pond, perfectly round, and completely frozen. Between incisions of light cutting through the dense pine, he observed as she brushed the snow from a low, flat boulder then sat gazing toward the glistening pond. Clouds moved overhead, masking then exposing the sun, and momentarily the scene surreally solarized. She suddenly turned in his direction, but did not see him. She removed a pair of battered ice skates from her satchel, stuffed crushed paper in the toes and dutifully wiped their blades.

The surface of the pond was patchy, her skates ill fitting. Adjusting to these hindrances may have contributed to her perilous style. After circling several times, she picked up speed and from a seemingly teetering position effortlessly cast herself into the liquid space. Her jumps had astonishing elevation; her landings were offset, yet precise. He watched as she executed a combination spin, bending and twirling like a mad top. Never had he seen athleticism and artistry so poignantly meshed.

There was a wet chill in the air. The sky deepened, casting a blue light on the pond. She opened her eyes wide, catching the blur of pines in the distance, the bruised sky. She skated for those trees, that sky. He should have turned away, but knew himself, recognizing the interior shudder when face to face with a delicacy: as a vessel, wrapped in centuries of rags, that he would unwind, surely possess, and raise to his lips. He left before the snow fell, catching sight of her raised arm as she spun, head bowed.

The wind picked up, and reluctantly she left the pond. Untying her laces she reflected with satisfaction on the day’s events. She had risen early, said prayers in the student chapel, and having already completed her national exams, retrieved her satchel from her locker and left without hesitation or remorse. Though a star pupil, precocious in her studies, she was completely indifferent. She had mastered Latin at twelve, easily solved complex equations, and was more than capable of breaking down and reexamining the most ambiguous concepts. Her mind was a muscle of discontent. She had no intention of completing her studies, not now or ever; she was almost sixteen, finished with all that. Her sole desire was to astonish, all else faded as she stepped upon the ice, feeling its surface through the blades into her calves.

A misted morning that would soon clear, making it perfect for skating. She made coffee and warmed some bread in a pan and called out to her Aunt Irina, forgetting that she was now on her own. On the way to the pond she noticed that despite the cold there were berries in the brambles, but she did not pick them. Wisps of fog seemed to rise from the ground. The light was silvery, and the pond took on a burnished quality, as if finished by munificent hands. She made the sign of the cross and stepped upon the ice, reveling in her solitude. But she was not alone.

An intemperate curiosity and the certainty that he would find her drove him to return. Undetected, he watched as she executed unique and intricate combinations, dangerously and poetically sporadic. Her rapture excited him; God had given breath to a work of art. She arched her body, spinning in descending and ascending spirals, shaking a bit of glittering dust from the star she was undeniably becoming. He soon departed but not soon enough.

She could not be sure of the exact moment she became conscious of his presence. At first it was no more than a feeling, then slyly one morning she distinguished his form, the colors of his coat and scarf, not entirely camouflaged. Sensing no ill will, she continued to skate, energized by his presence. No one, not even her aunt, had seen her skate, since she was eleven. As the days passed guardedly connected, they assumed their roles, each bolstered by the other.

Having freed herself from the enforced structure of school, and Irina gone, her days flowed into one another. She had little sense of time and lived by the approach and diminishing of light. She slept longer than usual and dawn was already breaking. Hurriedly she moved through morning rituals, grabbed her skates and headed toward the grove. As she approached the pond she spied the edge of a large white box set by the exposed roots of an old sycamore. She knew it must be for her, from Him. Dropping her skates, she removed a few heavy stones that had been placed on the lid and opened it slowly. Within layers of pale tissue was a mauve colored coat, a costly though somewhat old-fashioned garment,

ingeniously cut and lined with silky fur. It suited her perfectly, as the princess-style skirt was detachable, so to practice freely. With trembling hands, she examined every detail, marveling at the elaborate stitching, weightless fur lining, and its strange color that seemed to change with the changing light.

She slipped it on, surprised that despite the impression of lightness it provided the warmth of a miracle. She shyly searched his usual site, to register her pleasure, but there was no sign of him. Twirling about giddily, she experienced the melancholy luxury of solitary joy.

The unexpected gift suggested small hopes, a vague but promising hu

man connection. She felt a delight but also a fear of it, for it momentarily seemed to eclipse her impatience to skate. She lived only for skating, she told herself; there was no room for anything else. Not love, school, or scraping the walls of memory. Negotiating a bouquet of confusion, the lace on her skate broke in her hand. She quickly knotted it, then unfastened the skirt of her new coat and stepped onto the ice.

—I am Eugenia, she said, to no one in particular.

2

Cold rain streaked the windows of the cottage, then froze in strange patterns. There would be no skating this morning. Eugenia sat at the kitchen table and opened her journal. The first pages contained variations of the same set of lines, a poem of sorts, her loosely strung Siberian Flowers, written in the Estonian language of her mother and father, a language she had taught herself. She then turned to the back pages used primarily as an exercise book to practice English. Thoughts about skating, her aunt and former guardian Irina, and the parents she never knew. She intended to write more, but no words came to her, so she read and corrected what she had already written.

I was born in Estonia. My father was a professor. My parents had a nice house with some land and a beautiful garden that my mother tended with much devotion. My mother’s younger sister Irina lived in our house. She was leaving the country with a gentleman named Martin Burkhart. He was twice Irina’s age and very rich.

My father had a sense of impending danger. My mother had no such sense, she saw only good in people. My father entreated Martin to take me with them. Irina said my mother held me and cried for three days and nights. It comforted me to imagine being covered with my mother’s tears. That spring my parents were separated and deported from their village in Estonia. My mother was sent to a Siberian work camp but nothing is known about what happened to my father. I have no memory of these things. I only know what Irina has told me. Not the names of my parents or our village, Martin believed it was too dangerous. Everyone was afraid then, even after the war was over, but I was only a child and feared nothing.

Just Kids

Just Kids Auguries of Innocence

Auguries of Innocence Devotion

Devotion Year of the Monkey

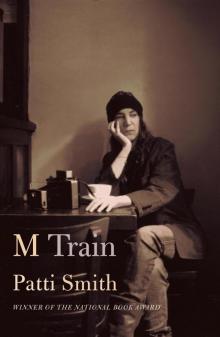

Year of the Monkey M Train

M Train Devotion_Why I Write

Devotion_Why I Write